In Northern Africa, in Algeria, about 180 miles south of Algiers, the Mediterranean, and the slashed throats of victims of the civil war, lies a seventy by forty* mile rectangle in the Sahara known as the Exclusionary Zone. In the Zone, sand undulates in dunes as wide as the horizon, but it is the oil below this sandy surface that is the Zone's raison d'etre.

I lived in an oil camp for one month in Rourde El Baguel, Algeria. I am not an engineer, geologist or driller, the primary occupations of oil camp residents. Nor am I a man, the primary gender of oil camp workers. I am an English teacher, hired to instruct Algerian engineers, bilingual in Arabic and French, in yet another language. Although the 13 hour days -- continuous without benefit of weekend-- were grueling and the camp decor Spartan and rules militaristic, I enjoyed my incredibly intelligent students and the idea that I was a part of something tangible and important: oil recovery.

There are many stories in the camp. There is the cafeteria where, my first night, I turned around with my tray to silence and hundreds of pairs of eyes staring at me. I felt like a crippled gazelle at a water hole frequented by lions. After a couple of days, however, everyone got used to the new girl, even though they continued to desalinate their conversations by curbing the use of colorful swear words.

I could describe the rolls of razor wires on our outer and inner perimeter walls, the military checkpoints, the rules against being on foot outside of the camp, the young guys patrolling with Uzis. Or I could complain about the emotional atmosphere, how everyone is pleasant but not really friendly, how even the bomb-sniffing dogs, barred from being petted or even spoken to by anyone but their trainers, seem lonely.

But I want to talk about the sand.

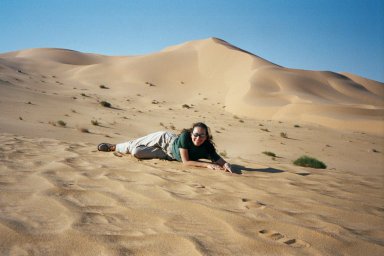

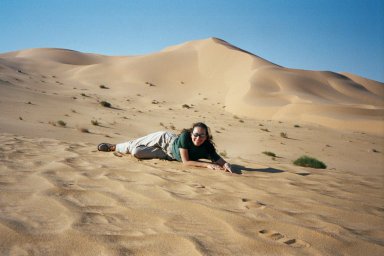

I can't tell you the numbers that correspond to the vastness of the Sahara. I am not a surveyor, the square footage doesn't interest me. If you look at the Sahara on a map, you'll see that it stretches through at least three countries. When you drive through it, as I did in a military convoy from Hassi Massoud to Baguel, you will automatically make comparisons to beaches and desserts you have visited. Your mind will lay mental photos side by side of the Southwestern United States or the dunes at Cape Cod or Wisconsin and other images until you realize that the Sahara is unlike anything you've seen. It is endless, and intimidating. Although the Sahara is actually quite fertile, the vegetation is limited to bits of scrub brush here and there. The sun produces a glare equal to a spotlight trained on a highly polished mirror.

Wear sunglasses or scream. In the camp, we live in trailers, the windows of which are covered over with closed metal slats. Although these closed slats prevent any fresh air from entering the trailer, they do not stand as an impenetrable barrier to the sand. Sahara sand is finer than beach sand. It coats the palm of your hand like makeup powder. Nothing, not closed windows, not wood, not duct tape can stop it from accessing an interior. When the sand blows in a vent du sable, French for a sandstorm, the individual grains penetrate the ears, the eyes, cover the scalp and scrape across the cheek like finely ground glass.

I left Baguel in a sandstorm. Oil workers work on a 4x4 rotation. Four weeks of 13 hour days followed by four weeks of vacation. A group leaves each Wednesday by bus to Hassi, but I had to stay behind. Kelli, the alternate teacher (each job is filled by two workers who work alternate months) was stuck in London with an expired Algerian visa. The embassy in London was closed due to elections, but our employer pulled some strings and a visa was issued to Kelli. Unfortunately, military escorts were suspended during the elections and, by Algerian law, expats cannot travel over land unescorted (anti-kidnapping measure). After standing by for half a day, while the sandstorm blew and the Pilates (small plane) couldn't get out of Hassi, I heard at 10 pm that another Pilates, from another camp, had set down in Baguel, and I would be leaving on it in the morning. At 6:30 the following morning, we took off in a mild sandstorm for the 30 minute flight to Hassi Massoud.

In the beginning, the sand saturated an upper layer of air so that it looked as if we were flying under orange clouds. Marc, the pilot, a French man with a large scab on the back of his balding head, flew close to the ground. I snapped pictures of Baguel as we left it, noting that the camp and oil apparati looked so small and cute in the surrounding desert. The wind picked up a bit and the plane begin to shake, and then bounce. And then shudder and drop. There were seven of us in the plane, seated in three rows. Another American handed back an air sickness bag that I gratefully took, just in case. The plane begin to pitch and roll more violently, and I saw that the American had grabbed onto a strap which he was hanging from with white knuckles. I stared at the sand below the plane, fixing on it as my reference point. Everything is A-okay as long as I can see the sand, I reassured myself. But then I lost the sand. We were in a whiteout, or an orangey-yellow out to be more specific. The plane jerked from side to side, and dropped, and we sat silently in our cloud of sand, trying to remember how close we had been to the ground before we lost visibility.

We couldn't turn around. We didn't have enough fuel to make it back to Baguel. And if you land in the desert, you're in the desert, in a sandstorm, in the Sahara. So we pushed forward. I wondered if the nervous American was praying. His face was very white. At first I prayed to land safely, and when that no longer appeared possible, I kept repeating "Make it quick. Please let it be quick."

And then, suddenly, there were the sand dunes again, and then storage tanks and gray metal buildings, evidence of oil production, which is what passes for civilization in this part of the world. The heavy set Algerian next to me said, "We're five minutes from Hassi," and he held up his splayed fingers so I would understand five. The nervous American turned and gave me a thumbs up, which I returned and smiled. The Algerian next to me said, in his melodic accent, "That was a very bad sandstorm." But his use of the past tense was not quite appropriate, since the sandstorm hadn't quite finished with us.

Marc got us on the ground even though the black ribbon of runway kept disappearing into the sand and reappearing like a magician's trick. As we sat on the runway, unable to taxi to the terminal because of the wind. I was told certain facts to tell people at home: we had been five minutes away from being forced down because of lack of fuel, the winds were 42 knots and we should have been told not to land, the large bleeding wound on the pilot's head was from an injury sustained in the sandstorm the night before. Marc got out from time to time and adjusted the plane to guard against the 42 knot winds tipping us over. At one point, we were moving very quickly, skimming over the runway, but backwards. The American talked about how screwed up Algeria was. Didn't they see us out there? Why didn't they send someone out here to rescue us? In America, they would have had a fire engine out here by now, etcetera etcetera. The Brits, Algerian and other American were quiet as we stared at the terminal standing fixed amidst the sandy swirl and dance.

We were rescued. A truck arrived and men wrapped in head cloths, hung from the wings for ballast, while others pushed us by the plane's wings to the terminal. When we arrived at the terminal, it took three men on each side to put the rope through the loop on each wing to secure the plane. I remember the nervous American losing it at this point and shouting, "Tie us down, for God's sake tie us down."

After exiting our tied-down plane, I clumsily navigated my way through the sandstorm by holding on to one of the men's shoulders. The nervous American insisted on carrying my suitcase. "I need the weight," he said.

On the charter from Hassi to London, I stared at the back of the seat in front of me and finally understood what it meant to have "the shakes." I stopped crying when I got to London, and from London to Dallas, I sat in business class and nursed a continuous round of alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. "I was in the desert, " I told the flight attendants. "I'm very thirsty." Many hours later, I ran my hands through my hair and wondered why my scalp felt all sandy, and marveled that my experience that morning in the small plane in the sandstorm was, for a moment, forgotten.

I go back to Rourde El Baguel, Algeria on May 12th. I will travel in country by bus.

P.C. Noble

April 1999